Earlier this month, millions of Americans tuned in to see which movies, actors and producers would take home an Oscar at the 2018 Academy Awards. It’s always an exciting event for film buffs, but in recent years the Oscars have gained the attention of statisticians and political scientists as well. That’s because since 2009, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has used a somewhat unconventional voting system to select its winners.

Earlier this month, millions of Americans tuned in to see which movies, actors and producers would take home an Oscar at the 2018 Academy Awards. It’s always an exciting event for film buffs, but in recent years the Oscars have gained the attention of statisticians and political scientists as well. That’s because since 2009, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has used a somewhat unconventional voting system to select its winners.

It’s called ranked-choice voting, and it’s a system that some American cities have begun using to elect their public officials as well.

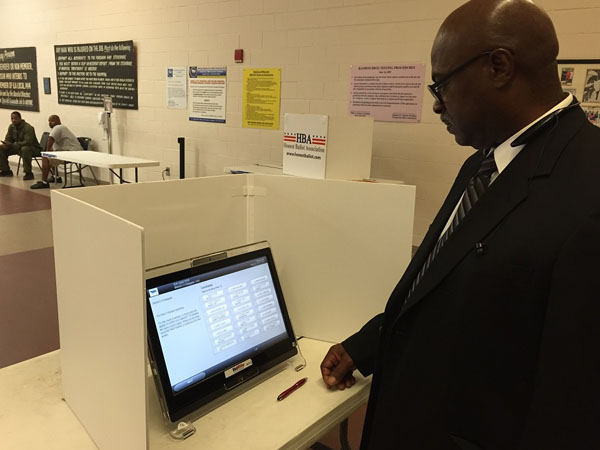

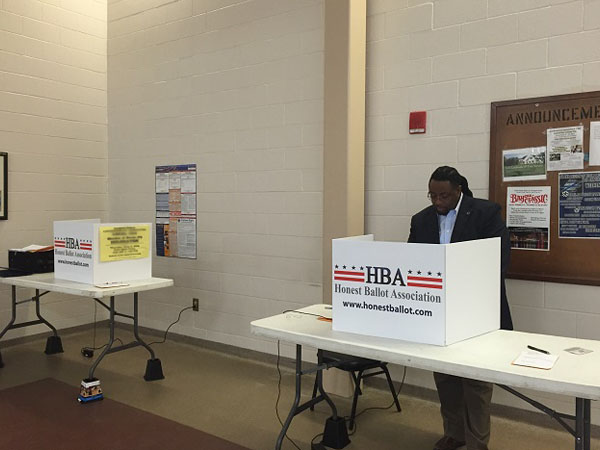

Also known as instant-runoff voting, ranked-choice voting allows voters to cast ballots for multiple candidates instead of just one. In this type of election, each voter ranks the available candidates in order of their preference. Once the ballots are submitted, election officials start by counting everyone’s first choice. If no candidate has the majority of the vote after the first round of counting, the candidate with the least number of votes is eliminated and election officials start counting everyone’s second choice. This process continues until a candidate emerges with an absolute majority—more than 50 percent of the vote.

If this seems a little complicated, check out the video below to see the concept of ranked-choice voting distilled into simple terms with colored sticky notes.

Now that we have a clear understanding of what ranked-choice voting is, let’s consider its merits.

The most obvious benefit of this voting method is that it always selects a candidate with the majority of the vote. In traditional elections with more than two candidates, it’s fairly common for a candidate to win with less than 50 percent of the vote. In 2010, for example, Republican candidate Paul LePage won Maine’s gubernatorial election with just 37 percent of the vote.

Because it allows voters to select multiple candidates, ranked-choice voting also tends to be more favorable toward third-party candidates that might not be viable in traditional elections. With this in mind, some political scientists have argued that ranked-choice voting could help end the unwavering dominance of the two-party system in national elections. After adopting ranked-choice voting in 2013, voters in Minneapolis elected a Green Party candidate to the city council.

Proponents of ranked-choice voting have also noted that the system is less prone to the “spoiler effect,” where voters are reluctant to cast ballots for a third-party candidate that might siphon votes away from mainstream candidates that are more likely to win. For an example of this effect, think back to the controversy surrounding Democrats who voted for Green Party candidate Ralph Nader in the 2000 presidential election, thereby reducing the number of votes that were cast for Democratic candidate Al Gore.

Alright. Ranked-choice voting certainly has its appeals, but what are the chances of it gaining widespread adoption in American elections?

Well, that remains to be seen. As of March 2018, ranked-choice voting is used in 12 American cities, and more than 50 colleges and universities. At least three more cities are currently in the process of implementing ranked-choice voting into their electoral systems. It has yet to be used in a statewide election, but that’s about to change.

Recently, Maine became the first state in the union to approve the use of ranked-choice voting in a statewide primary election. In June, residents of Maine will decide whether they want to use the ranked-choice voting system in November’s federal elections as well. If the measure is approved, Maine’s upcoming midterm election could serve as a litmus test for other states that might also be interested in adopting ranked-choice voting.